post

Training manuals are essentially of a time and place, yet change (time) and constructions of childhood (place) rarely feature. Manuals and training cannot stand alone, they need to be combined with experiential learning including how to respond to change.

Since the early 1990s, following the UNCRC, there has been a proliferation of manuals around children’s rights, participation, measuring and evaluating ways of working with children. Manuals tend to be the outcomes of projects, promoting organisations and their models of work, and fulfilling funding obligations.

I have come across, used, taken activities and ideas from manuals in my work with children and adults since the 1990s. For Rejuvenate, I went back and looked at the increasing variety of examples from over the past 30 odd years.

They vary by:

- theme (rights, participation, research, peer-to-peer, safeguarding etc.),

- practice areas (community development, health, radio, newspaper etc.),

- classification of children (girls, `street children’, adolescents, early childhood, youth),

- formats and

- organisations.

Manuals may be of different types, but essentially focus on `how to’ such as how to do participation, child/youth-led community development, peer-to-peer learning, research, work with girls, with `street children’, how to measure and evaluate. More recently some attend to policy and community context.

Many activities reappear in different publications. Types of format have shifted over time, and range from very specific (activities timed to the minute in fixed sequences) to structured compendia offering pick-and-mix activities. Some constitute a complete course for a trainer, for self-learning or for both. Some have separate facilitator guides suggesting a graded progression from trainee to trainer.

Change

But manuals are essentially of their time and place. Many are essentially artifacts recording practice and ideas at a particular time. They could be mined to show development of actions and responses in a variety of areas of children’s rights and work practice. Yet time and place are considerations that they rarely, if ever, feature, despite change being a universal experience and a main aim of training.

The change implicit in manuals is change in practice, policy, systems, individuals, communities. Whenever the manual was compiled, for those using it the starting point is now, this moment. Yet despite the interventions being focused on children, the local constructions and meanings of childhood, the expectations of their behaviour are also rarely, if ever, considered. Some attention might be paid to diversity, but are the complexities of approved behaviour and the definitions and experiences of marginalisation included?

Childhood constructions

The key to all this is understanding and working with local conceptions of childhood: the local stereotypes and norms of diversity, notions of deviance, ideas of marginalisation and exclusion. Childhood has a particular construction by place, locality and inhabitants. Childhood constructions, and expectations of children at different ages, gender, disability, wealth and other status change over time. Yet manuals which may aim to shape changes in a particular way, through changing (improving, developing) people, practice, policy, law, systems, do not necessarily take these constructions into account.

Research could help uncover local constructions of childhood, but would need to be done with adults, and the goal of much research involving children is to capture views and opinions and voices, to policy and practice related ends, without time to first consider community and family expectations.

Why is this important?

The manuals, whether curricula or compendia of resources, aim to train individuals, groups, colleagues, staff. Yet for adults to work with children now, they need to unpick personal assumptions, understand their perceptions of childhood, recognise their expectations of diverse children, their views of marginalisation, and of children who do not conform to expectations.

Adult experiences of being a child are not the same as experiences of children today. Children’s rights and participation are about power: the location of power is in constructions of childhood, and both change over time. Yet these crucial aspects are not the bases of manuals or training, despite childhood and youth being driven by change. They grow and become adults in a different time and context, and this change is continuously restarting.

How to learn practice

Apart from incorporating local childhood constructions, the form of learning needs to extend beyond manual-based workshops to experiential learning. Understanding and dealing with power dynamics, creating spaces, facilitating, are what training and manuals may aim to develop. In practice, the reality of doing this, taking that first step into a group of children, speaking, answering, is different from the workshop module.

Skills and knowledge are needed but practice needs to be reflective, to change, to throw away the plan that isn’t working, to devise new. Ethical principles and standards can run throughout and need to be known and understood as a vital framework of limitations, ensure no harm, no discrimination, and enable all, including the most marginalised.

But the ability to change in response to circumstances is essential. Experiential learning based on change and reflective practice may cost more time and money, is easily omitted in positive, `can do’ approaches apparently favoured by many funders, and doesn’t sit easily in structured, time-bound plans. Yet without recognising and incorporating local constructions of childhood and the fact of change, the need to respond, the ability to reflect and change practice, the `how to’ is functioning at the mechanical end of a continuum.

The manual can only be one part of developing practice, to be mined for ideas and resources. Constructions of childhood are not fixed. Communities, practice, policies and cultures change. Understanding self perceptions and local constructions, as well as institutional assumptions, are essential for individuals, and for organisational practice.

The point is to take on change and experiential learning, not to follow the manual. The process of giving away decision-making power, and responding to what children and young people say and do, is best learned through the practice of experiential learning and reflection.

As a starting point, one could look to the basic requirements principles outlined in paragraphs 132 -34 of the UNCRC General Comment on the right of the child to be heard. Of course, it is possible to produce a set of essential questions to be asked, to lay the ground before embarking on facilitation. But that would be yet another manual suggesting –“do it my way”.

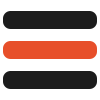

Photo credit: Andy West – 2010. A child’s drawing of a shop in a square in Lhasa, Tibet where ‘street children’ pick up caterpillar fungus (yartsa gunbu) dropped by merchants passing through. The fungus grows in the Himalayas and is worth a fortune as it’s used in medicine in China.