post

This blog draws on ideas from the Rejuvenate Working Paper (Johnson et al.)

This week’s news and social media feeds are filled with images of world leaders and protesters attending COP26 in Glasgow, many recognising the significant role that young people have played in the climate change debate. The agenda currently on the table would not have been possible without movements such as Fridays for Future, through which children and young people have been persistent in delivering a powerful and urgent message to world leaders. Friday 5th November is set aside in the Presidency Programme to specifically discuss ‘youth and public empowerment’.

When we look at climate change debates within the wider field of child and youth rights and participation, it’s clear that the political agency of children and youth is beginning to be recognised. This is a major development, and we need to take the lessons learned here into other conversations and ultimately, towards a radical shift in our social hierarchies. This shift is already underway in gender and race politics, and there is growing will to interrogate the assumed social norms that have long underpinned our social structures.

Perhaps the most deep-rooted of these norms is adultism, an oppression of children and youth simply because of their relative age. Adultism is a sticky and residual belief system, but one that has been excitingly upturned in the climate change conversation.

One of the most significant barriers to dismantling adultism is the underlying assumption that the power that adults exercise over children is always legitimate and justified, an assumption similar to those historically mobilised to justify other social inequalities and oppressions of race, gender, disability, class and sexuality. Age-based social inequalities are complicated by children and young peoples’ evolving capacities, and the need for adults to recognise and support these.

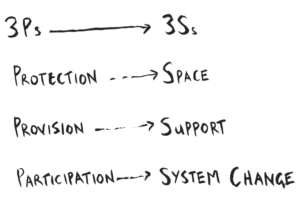

Compiling the Rejuvenate Living Archive enabled us to draw out key lessons from successful examples of child-led work, across a variety of projects, organisations and literature. Many examples included in the archive recognise that children find relationships with peers and adults helpful in navigating uncertainty and change. In our working paper (Johnson et al., 2020), we propose a shift in our thinking around children and young people, beyond the 3 Ps (protection, provision and participation) proposed by the UNCRC, towards the 3 Ss:

Space

We need to create and build on existing safe spaces for children and young people. These spaces – both existing and those re-imagined – allow them to build confidence through dialogue with peers and to engage constructively with adults in positions of power. We also expand the concept of space to mean creating space in project and decision-making processes to meaningfully include children and youth.

In climate change activism, children and youth have claimed space through their practice of protest. By taking to the streets every Friday, the youth organisers and participants of Fridays for Future have compelled adults to listen and act, resulting in children and youth being invited to other spaces, such as COP26. These achievements are notable and represent a tangible challenge to adultism. However, we need to work harder to give space to children and youth to contribute to the many other issues that affect them, and their communities.

Support

Our research consistently surfaced examples of children and youth asking adults to listen to and support them. It revealed that young people think not only of themselves but also their communities, and future generations. In addition to providing children and young people with space, adults have a responsibility to support children and youth to apply their agency.

In Plush’s paper ‘Amplifying Children’s Voices on Climate Change: The Role of Participatory Video’ she explains a process by which children were supported to advocate for climate change adaptation that was relevant to them and beneficial to their entire community. With the support of adults, children and young people were able to influence local and national policy.

System change

Social change requires confronting social norms and structural inequities based on hierarchies including adultism. Social attitudes towards young people in many global contexts assume they should be seen and not heard. Children and young people are thought to be part of social problems rather than potential allies in finding the solutions to these problems. Adults need to be engaged to change their own perspectives and the harmful institutions and social norms that make young people’s positive contributions to decision-making invisible.

In the climate change conversation is a good example of a context in which adults have begun to recognise the importance of giving children space and support, but system change has yet to take place. Now is the time to harness and extend this powerful example. We need to proactively work against our deep-rooted social norms everyday in order to unlearn, and then re-learn, how to give children the space and support, and system change, so urgently needed by us all.

Photo credit: Greta Thunberg at the front banner of the FridaysForFuture demonstration Berlin, 29 March 2019. Photographer: © Leonhard Lenz. CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain